As a follow-up from the Climate Action Conference Peter Bruce organised an amazing field trip to Church Bay at the breath taking Tutukaka Coast. A group of enthuisasts was hosted by Hamish Clueard from the Ngati Wai hapu and Glenn Edney, both founding trustees of the “Te Wairua O Te Moanui – Ocean Spirit Charitable Trust”.

The first part of the trip covered the new Eckelonia Kelp Restoration Project in Church Bay and the second part about land restoration from farm land with sediments running into the harbour to fertile, food growing land.

Eckelonia Kelp Restoration

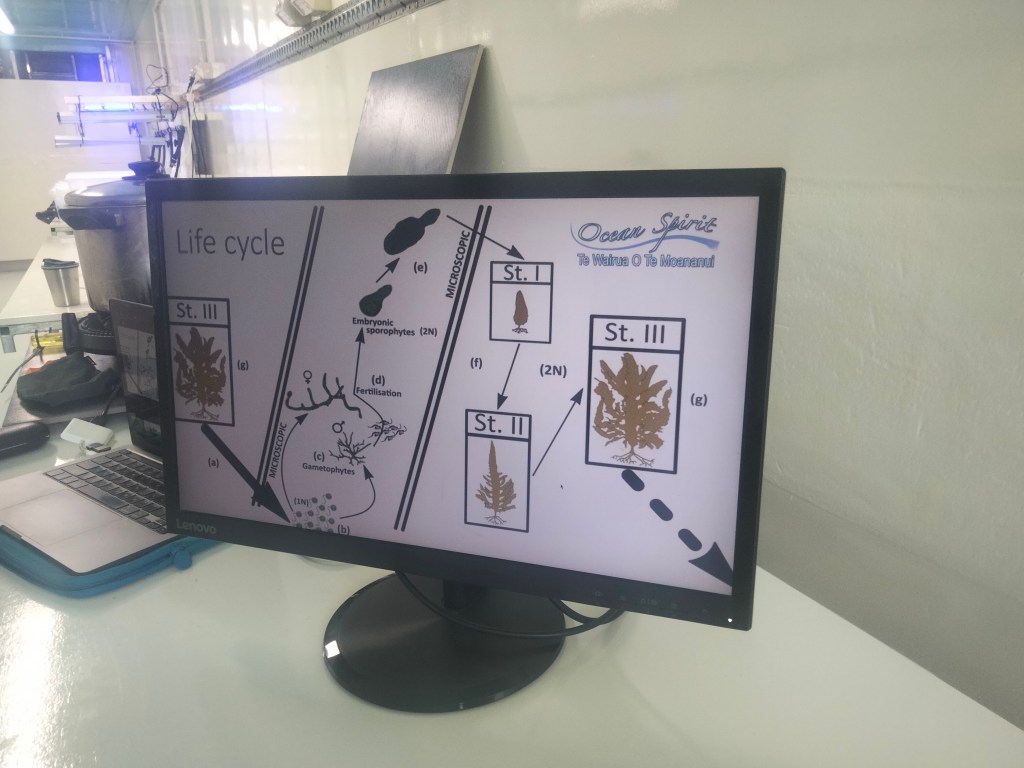

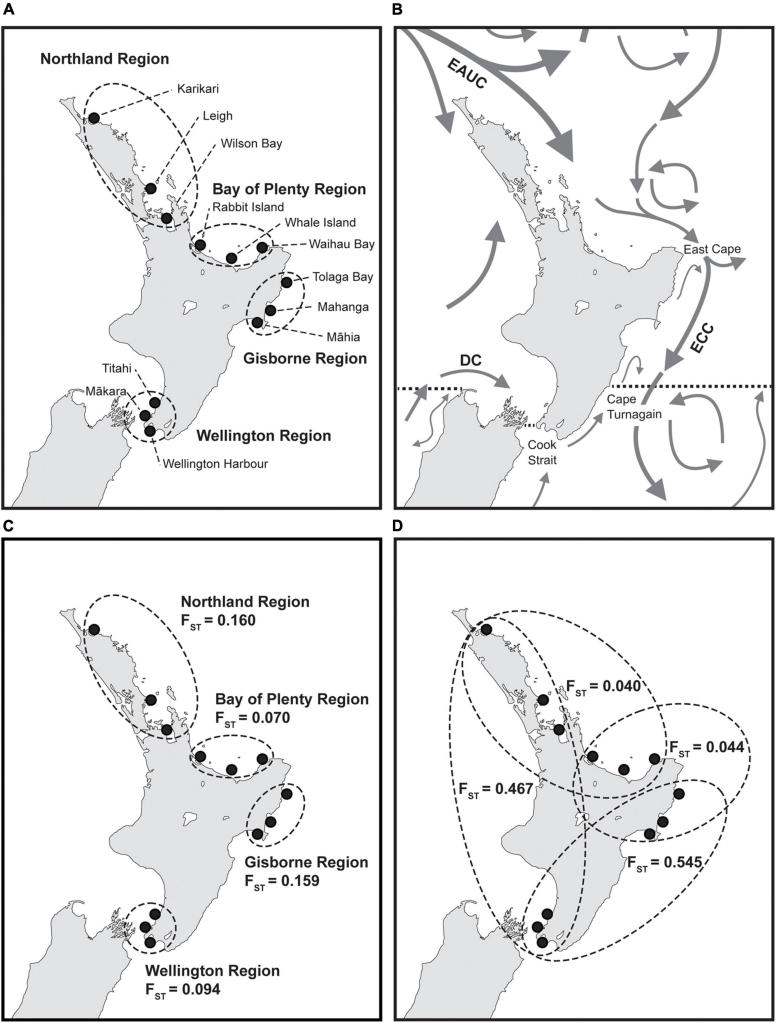

The project started in 2018 and got good traction the last two years. The Founders purchased an old refrigerated trailer, planed the ground at hapu land in Church Bay and got working on the land. Over the last year they have done three kelp restorations in the Tutukaka Harbour. The project is scientifically supported by Professor David Augirre’s Team at Massey University from Albany, Auckland. They use the Norwegain Green gravel approach.

The idea is to source local kelp spores, and then rear them in an onshore lab to an adolescent size of about 10cm and then plant them in the right spots in the harbour.

But first a bit of background on the wider ecological challenge why all this is important.

With macro activities like commercial and recreational fishing, the predators which keep a bay like Tutukaka in balance get disrupted. Stock of snapper and crayfish have been reduced over the last decade dramatically. This can be confirmed by anecdotal evidence from many local fisherman or in reports on the Hauraki Gulf (a good read if you are interested in ocean ecology and lessons learnt in a NZ context).

In a healthy coastal environment like in Northland, snapper and crayfish control kina populations. Kina feeds on kelp. In Northland the Ecklonia Kelp species is the most widely spread kelp. And is part of the Church Bay Kelp Restoration project.

First a bit on Ecklonia Kelp:

The kelp consists of a stipe and blades. Ecklonia grows between 5-7cm/ week. Their ideal growing temperature is approx 17 degrees. 21 degrees is close to the maximum temp they can tolerate, but that will vary a bit from place to place. The time period from gametophyte fertilisation (the mating bit) to sporophyte (the baby kelp) is 12 to 14 hours, not days. The parts of the kelp are the stipe (almost like a tree trunk) and blades (like tree leaves).

In regards to the depth range of the kelp, they can grow from just below the low tide line, down to 30m in very clear water. More generally these days though the max depth on the coast for ecklonia is 20m or less due to the sedimentation blocking out sunlight. When the blades folded over is in reference to them breaking the surface at very low tides, like Spring tides, where the top of the stipe is at the surface and the blades are laying flat on the surface.

Baby kelp like to stay together and protect each other. The Ecklonia has male and female spores. When they mate, the create new kelp within a period of 14 days (not nine months as with humans..). The blades can fold based on circumstances. Some times you can see the blades folded and floating on the surface. However, the Eckonia kelp can do that only a specific occasions like king tides or massive swell events.

Sources: Nepper-Davidson et al (2021) and Glenn Eadney

Interestingly, adult kelp is more vulnerable against storms than adolescent.

The healthiness and growth of the Eckelonia kelp is determined by a lot of factors. River and bank run offs and the change in nutrients is one aspect. When big swells and storms come into the bay lots of deposited sediment can be mixed up and redistributed. Sometimes this can be seen up to 3km offshore towards the Poor Knights. As described above the kelp is naturally eaten by kina. If that is done in a balanced way, that is quite allright. If the kina population gets too big, they can mow down most kelp in a short period of time.

In good conditions the kelp lives for about 10 years. It’s photosynthesis produces oxydification which is important for the gas balance of the coastal waters.

According to Glenn, phytoplankton has been reduced by 45% and kelp by 30% globally (Include REFERENCE).

And now a bit on Kina.

Kina is a very healthy, traditional food source for Maori. Kina is a good source of Iodine, Selenium, Vitamin B6 and VitaminA; and a source of Magnesium, Phosphorus, Potassium, Riboflavin (vitamin B2) and Vitamin E. Kina includes bioactive oil – like many fish, kina contain omega-3 fatty acids, which benefit heart health and reduce arthritis, diabetes and asthma. However, kina oil is likely to have enhanced anti-inflammatory properties compared with standard fish oil. So in a nutshell, Kina is good for you.

From the bloomsom of the kowhai trees to the pohutawaka bloosom, kina roe is developing ready to spawn. That is the time when the kina is the tastiest. It is not very yummy when it is starving and coming from kina barrens.

A kina barren is an area where the kina has eaten most kelp, because snapper and crayfish have not been able to control the kina population. Once the kelp is gone, the kina eats the little stuff which remains. Once that is gone, the kina population will dwindle too. All that is not good for healthiness of the coastal waters.

There are different approaches to fix the symptoms of overfishing, one is culling kina (killing them on site, like in the Hauraki Gulf at the Noises – see Noises blog and publication on “efficiency and effectiveness of different sea urchins removal for kelp restoration” a collaboration of Nick Shears, Kelsey Miller and Arie Spyksma, 5-40% kelp cover returned in 2yrs) or removing them and eating them. The latter is exactly what Hamish & Glenn are doing. The had

12 x divers, cleared an area of 20m x 15m in about 1.5hr and collected close to 350kg of Kina. This fed the local hapu nicely.

One Kina roe has about 1,000 spores each. During the lunar cycle the spawning begins.

When the team cleared the above area for kelp planting, the Kina took over three (3) months to come back.

For more information, check out climate action website.

“Mena kei te hauora te moana ka pera ano te hauora o te iwi” – If the ocean is healthy so too will the people be healthy.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

The second part of the visit was even more exciting when we visited Hamish Clueard’s whanau land and learnt about the South American Chinampas. This is an S-shaped waterway with floating food gardens. This will be described in more detail…

Chinampas are an innovative agricultural technique that originated in Mesoamerica. These floating gardens have been used for centuries to grow various crops, offering a sustainable and efficient solution to feeding communities. The ingenuity and resourcefulness behind the creation of chinampas highlight the human ability to adapt and thrive in challenging environments. By harnessing the power of nature, chinampas provide fertile soil, reliable irrigation, and increased crop yields. This ancient farming method not only sustains traditional farming practices but also serves as a testament to the resilience and wisdom of our ancestors. Embracing the positive impact of chinampas can lead us towards a future of sustainable food production and a harmonious coexistence with nature.

First some background … chinampa means small, stationary, artificial island built on a freshwater lake for agricultural purposes. Chinampan was the ancient name for the southwestern region of the Valley of Mexico, the region of Xochimilco, and it was there that the technique was—and is still—most widely used. The Aztecs used chinampas to make the best use of their space, especially as their population began to rise. Chinampas were sustainable, yielded a high output of food, and provided more land for the Aztecs to live and farm. Chinampas are created by staking out an area in shallow water, then fencing in the area between these stakes with wattle of branches and reeds. These underwater fences are used to contain mud, lake sediment and decaying organic matter.

And this latter effect is the key reason why Hamish and his sons have been working their whanau land for many years. Their forebarers at the beginning of the last century cleared the valley, drained it and turned it into farmland. However, it came apparent that the run-off from the land and the sediment deposited into the Tutukaka Harbour were very harmful to flora and fauna. Once Hamish’s family realised this, they sprung into action. They got the diggers out and changed the nature of the valley for good. The first thing they did was to block the direct run off from the land to the sea. The Chinampas were a welcome indigenious method to minimize negative environmental impacts and maximize food production in limited area. Hamish has invited local schools to start planting food gardens on the floating Chinampas in the valley.

In addition to absorbing the run-off of the valleys hills, Hamish is trying to restrict and revitalise the waterways at the same time. One of the steps is to plant vegetation which is shading the stream going to the sea. The idea is that shade prevents the obnoxious aligator weed to spread. Another project is to replace a 70m pipe at the beach to allow native fresh water fish to swim up the stream again. We walked through the dense bush up to Hamish’s whanau land boundary and saw where those fish used to get to. The whole project is about restoring the land and giving local flora and fauna a chance to come back. I am not really a farmer, gardener and only partially understand the extent of the work which gotten into this project. But I can surely see the impact. Very healthy bush is coming back, birds are singing happily every where and almost land on your shoulders. To me as a native from the Sauerland (a small rural area in the middle of Germany) to me this valley seems like the valley of dreams and magic. Please support Hamish and his whanau to clear away more weeds and make the local freshwater fish come up the river again. As Hamish said, this is the ulimate measure of success of this land restoration project. To me this should be a role model to other valleys which deposit a lot of partially toxic sediment into our wonderful Tutuaka Harbour.

I am sure there will be lots of working bees and school kids needing support to plant the amazing Chinampas in Church Bay …

Many thanks again to Hamish Clueard and Glenn Edney for allow us to visit their inspirational projects hidden in the magical Church Bay Valley and foreshore…

I would have loved to join this field trip! Very pleased to see some traction restoring Ecklonia beds.